The Canarian master shipwright Agustín Jordán was the lead figure in the restoration of the Scottish fishing vessel Margaret Alison. From the summer of 2018 until its relaunch in January 2023, he led the project with the support of a dedicated team of volunteers, who worked under his guidance at El Moll in the Port of Arenys.

A deep passion for wooden boats and traditional craftsmanship drives Agustín’s mission to preserve maritime heritage. Below, we revisit two interviews conducted while he was working in Arenys: the first, in the summer of 2018, by journalist Elena Ferran for El Punt Avui, at the start of the restoration; and the second, in the autumn of 2022, by Sílvia Abril for the TV show La Recepta Perduda, when work on the new deck was in full swing.

– Agustín Jordán on “La Recepta Perduda” (YouTube clip with subtitles)

EL PUNT AVUI – August 21, 2018

AGUSTÍN JORDÁN, MASTER SHIPWRIGHT: “The love for maintaining wooden boats has been lost”

Agustín Jordán is one of the last traditional boatbuilders in Lanzarote, a trade at risk of disappearing. His expertise has brought him to the Port of Arenys, where he is restoring a historic Scottish fishing vessel.

Is maritime heritage at risk?

Yes, and people should become more aware of the importance of these vessels. Skilled craftsmen are disappearing, and unfortunately, it’s difficult to find young people willing to learn wooden boatbuilding. Since 2002, I’ve been running courses in Lanzarote to introduce this craft to those who want to learn.

It’s hard to find shipwrights here. Is it the same in the Canary Islands?

Twenty years ago, there were still some, but with the decline of the fishing industry, many left the trade, and their children didn’t continue. It’s a very demanding job. In May, we completed a nine-meter boat after a full year of work.

This isn’t a trade where you can rush…

No, it must be seen as an art—because it is one. The essence lies in designing and building boats together with the sailors, crafting them to fit their needs. Repairing or maintaining fiberglass or steel boats is something entirely different.

Has that essence been lost?

Fishermen don’t really care what kind of boat they go out to sea in. The love for maintaining wooden boats has been lost, and we need to encourage people to build and appreciate them. In the past, fishermen often built their own boats, especially in island communities where fishing was vital for survival.

Did almost everyone own a boat?

Those who could afford one. It was difficult to get wood on an island with no forests. People would gather driftwood from the shore.

Where did you learn the trade?

It wasn’t passed down in my family. From a young age, I was drawn to the sea and boats. To me, the men who built them were the smartest people in the world. My brother was friends with master shipwright Vicente Dorta, who built the best boats on the island. But before that, I spent four years apprenticing at Evaristo González’s workshop. I built my first fishing boat when I was seventeen. When Master Dorta saw it, he had no doubts about teaching me how to draft boats. It was my passion.

And that passion still burns…

I often say it’s like an illness that worsens over time—I just want to build more boats. Since 2008, when I came to the Barcelona Boat Show to demonstrate boat drafting, I’ve realized the need to train people who want to build their own boats. Self-building allows them to dedicate as much time as they need, and the results can be real masterpieces.

That’s what brought you to Arenys. How is the work going?

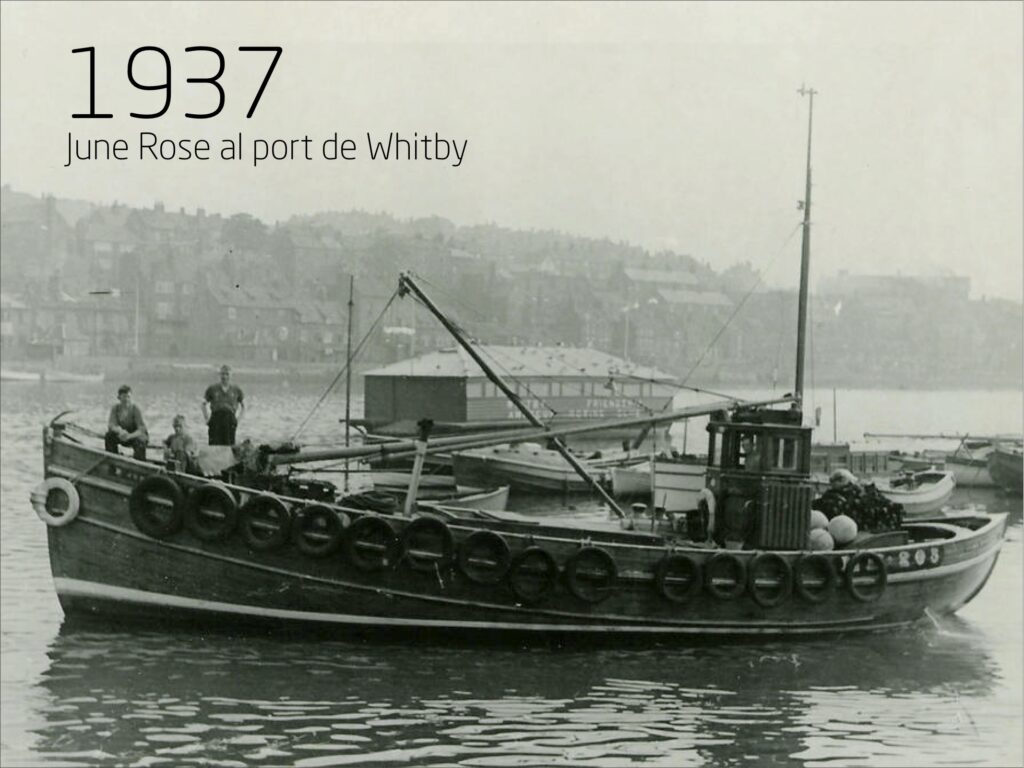

We are restoring the Margaret Alison, a Scottish fishing boat built over eighty years ago. When the team from El Moll invited me to take on the project, I didn’t hesitate—it would have been a crime to let such a historic vessel be lost. We are taking templates of the damaged sections and rebuilding them with the original materials, mostly oak and Nordic pine, preserving every detail to maintain the boat’s authenticity.

Do you see similarities in construction techniques?

This is a strong and robust boat, built for the rough northern seas. But in terms of structure, the techniques are quite similar, and shipwrights always incorporate methods from different regions. In the Canary Islands, when our fleet fished off Mauritania, we would buy boats from different places—especially from the Basque Country—and improve them.

With fleets being scrapped, it’s hard to keep the trade alive.

Yes, in the Canary Islands, all the traditional wooden tuna boats were dismantled, while subsidies went to more toxic and polluting materials. The bureaucracy involved in building wooden boats hasn’t helped either—you end up needing so many permits that they cost more than the boat itself. In the Canaries, talking about a wooden boat is like mentioning the devil. But we are the first ones concerned about safety, and there should be more trust in this craft. The industry needs to rethink its future because with so few incentives and how long it takes to learn the trade, people get discouraged.

Now you’re working with volunteers and apprentices…

Yes, they appreciate the craft and want to learn techniques that have been passed down through generations. My team includes retired fishermen who spent their lives at sea, as well as young people who see this as a possible career. I have no secrets—I teach them everything I know.

What’s the largest boat you’ve built?

A 16-meter fishing vessel called Gla, built for the Mauritanian coast. The Margaret Alison is similar in volume.

Will the Margaret Alison last another 80 years?

It’s possible that it will survive for several more decades, but by the time it needs another major restoration, there may be no shipwrights left. Heritage preservation efforts must also include support for the skills and trades that keep maritime traditions alive.